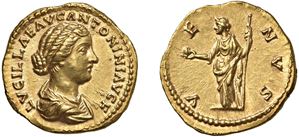

RIC 443. Calicó 1444. Rare.

q.FDC.

Shipping only in Italy.

In the final years of his life, marked by severe physical difficulties, Hadrian was forced to confront the delicate issue of imperial succession. In 136 AD, his choice fell on Lucius Ceionius Commodus, consul in office that year, who took the name Lucius Aelius Caesar. However, he lacked solid military or administrative experience; for this reason, he was granted tribunician powers and sent to the Danubian border, tasked with governing Pannonia.

Hadrian's dynastic project, however, did not have time to materialize. Aelius died prematurely in 138 AD, once again leaving the emperor, now gravely ill, without a designated heir. His appointment had already aroused perplexity and discontent, further fueled by the scandal that had erupted a few years earlier, in 130 AD, when Hadrian had promoted the establishment of a cult and the issuance of coins in honor of Antinous, the emperor's young favorite, who had drowned in the Nile during an official journey. In this climate of suspicion, the idea spread that Aelius's choice had been made against general opinion and was motivated solely by his good looks.

Some early scholars even went so far as to hypothesize, as Carcopino did, that Aelius was Hadrian's illegitimate son, but this interpretation has since been widely refuted. It is more likely that Aelius had won the emperor's esteem thanks to his cultural education and the sophistication of his interests, in keeping with Hadrian's attention to the arts and intellectual life. After his death, Hadrian adopted Aurelius Antoninus, destined to become emperor under the name Antoninus Pius, but he also required him to adopt Marcus Aurelius, son of Aelius and Hadrian's adoptive great-grandson, thus ensuring dynastic continuity.